Reading Between the Bars

An In-Depth Look at Prison Censorship

Key Findings:

The widespread lack of record-keeping of bans by prison authorities obscures the full scope of the problem.

Prison officials cite two main rationales for censoring literature based on the content: 1) sexual content and 2) security. We found that these rationales are applied broadly to censor scientific, creative, historical, and other forms of literature.

Content-neutral banning is on the rise. We identified, in the past 8 years, a steep rise in the number of prisons that practice content-neutral banning, specifically “approved vendor” policies, a practice that limits the booksellers incarcerated people can purchase literature from and largely prohibits free and used literature.

Appeals processes can be opaque and confusing, leading to few attempts and low rates of success. Through analyzing prison banned book lists and prison narratives, we found that the processes currently available for incarcerated people and publishers to contest prison book bans do not meaningfully limit or challenge this censorship.

We end the report with several recommendations for challenging carceral censorship at the state and federal levels.

PEN America Experts:

Senior Manager, The Freewrite Project

Intern, The Freewrite Project

Introduction

At Nash Correctional Institution in North Carolina, a series of low-lying brick buildings ringed with barbed wire fencing, parking lots, and stands of pine trees, Duawan Wesley McMillan eagerly awaited two books in the Colored Pencil Painting Bibles series that his sister had sent as gifts. McMillan’s sister, who lives in the sleepy village of St. Pauls, North Carolina, population 2,000, received notification through Amazon in February 2023 that one of the books was delivered. Excited for her brother to receive these gifts, she called the mailroom at Nash four days later and was informed that her brother hadn’t yet received either book. Mailroom staff told her that he would receive the first book later that day. Two days later, her brother still hadn’t received either book, so she called a second time. At this point, McMillan was given one of the art manuals, but when he received it he noticed that pages were torn out. When he questioned the missing pages, the mailroom staff told him that the book had arrived in that condition.

Six days after receiving the first art guide, he received censorship paperwork and was told that the second book was denied because it had been mailed from a residential address, despite both books having been ordered at once from Amazon. But the time had already lapsed for him to appeal the decision—by six days. McMillan was told that he could either pay $17.05 for the drawing book to be mailed back home or let it be thrown in the trash.1Letter sent from Duawan Wesley McMillan at Nash Correctional Institution (North Carolina) to PEN America, March 24, 2023.

Carceral censorship is the most pervasive form of censorship in the United States. The Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) and the departments of corrections (DOCs) in all 50 states and the District of Columbia censor literature – and the rationales they employ for censoring books are vast and varied.2In this report “Washington” will refer to the state and “District of Columbia” refer to the capital. Prisons ban specific titles, based on the alleged threat of their content – a tactic similar to that of book banners who have targeted public schools and libraries in the past two years.3Meehan, Kasey, and Jonathan Friedman. “2023 Banned Books Update: Banned in the USA.” PEN America. April 20, 2023, https://pen.org/report/banned-in-the-usa-state-laws-supercharge-book-suppression-in-schools/. Prison banned book lists in many states contain thousands of unique titles; any incarcerated individual in that state is barred from reading any title on the list.

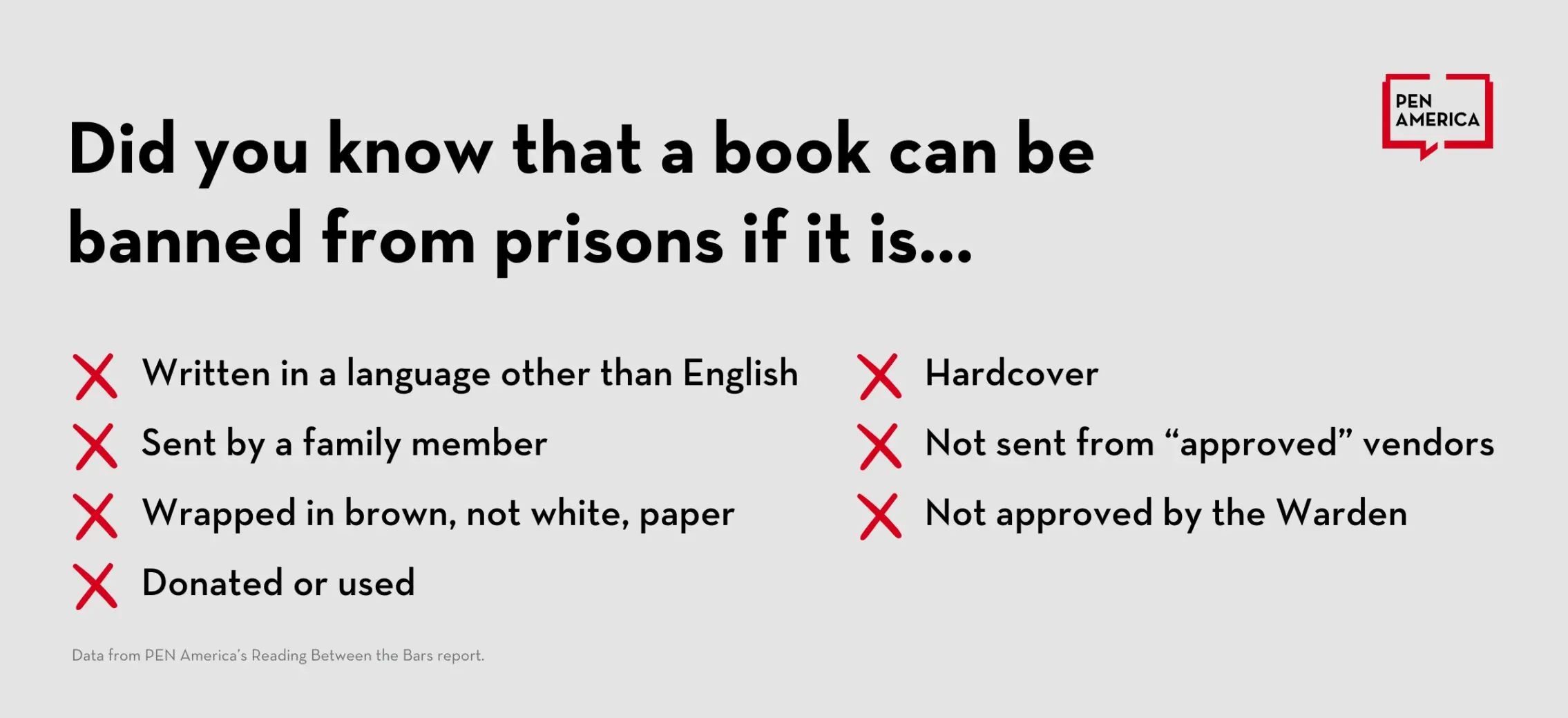

In addition to content-based bans, there is a second, even more pervasive form of censorship unique to prisons: content-neutral restrictions, which categorically reject and restrict literature based not on its content but a host of other factors, including but not limited to the sender, a book or magazine’s appearance, or whether the incarcerated person obtained permission to receive it from a prison administrator. This content-neutral censorship is not what many first think of when they hear the phrase “book ban.” However, these policies have the effect of denying incarcerated people literature by limiting book deliveries per month per person, limiting the quantity of literature in a person’s cell or locker at a time, returning literature to senders if they’re not mailed in white paper or other specific packaging requirements, limiting literature purchases to a small list of state “approved” businesses, prohibiting the delivery of free books, used books … Prison censorship is distinguished not just by its targeting of specific titles or topics, but by the sheer number of tools in the censors’ toolbox.

Prison officials commonly justify censorship as necessary for rehabilitation and the maintenance of safety and security. The rationale that censorship should be used to accomplish these goals is specious—and yet often receives little scrutiny.

In a letter to PEN America, William Daniels Jr., incarcerated in Kentucky, wrote: “Within the Prison Industrial Complex, I am told that ‘SECURITY’ must be maintained at all costs, even at the cost of my education, of opportunities that could well lead to my betterment, potentially keeping me from returning to this side of the razor wire fences, or who knows, . . . perhaps even finding my own humanity.”4Letter sent from William Daniels Jr. at Northpoint Training Center (Kentucky) to PEN America, March 31, 2023.

Prison censorship normalizes the idea that reading can be dangerous. Robert Greene, a self-help author whose books are banned in 20 state prison systems, told PEN America that prison censorship is “something that spills out beyond the prison system. And it’s a form of control. It’s the ultimate form of power of manipulation. So the hypocrisy of saying, This is a book that’s dangerous for you—whereas they’re the ones that are completely controlling the dynamic and giving you access to only certain amounts of information—is very frightening. That’s how totalitarian systems operate.”5Robert Greene, in discussion with the authors, Zoom, July 26, 2023. Robert Greene is the author of New York Times best-selling books, including The Art of Seduction and The Daily Laws.

Reading Between the Bars builds on PEN America’s benchmark 2019 briefer on carceral censorship, Literature Locked Up: How Prison Book Restriction Policies Constitute the Nation’s Largest Book Ban, in which we first delineated the difference between content-based and content-neutral censorship. Reading Between the Bars and the accompanying indexes lay out how previously documented policies have adapted and changed in the intervening years, and provide updated information on censorship policies in all 50 states alongside insights gained from prison mailrooms, prison book programs, and personal narratives from incarcerated individuals experiencing censorship.

In the past two years a movement to ban books in public schools and libraries has spread across the country. The trends have garnered significant public attention, representing as they do, a radical change from years prior. As PEN America has stated previously, book banning and restrictions on literature must be opposed because when society accepts the basic premise that ideas and information can be a threat, it opens the door toward the suppression of learning and information more broadly.

As a free expression organization, we are adamant that this standard must also apply to prisons. Carceral censorship should be opposed not only for its effect on incarcerated people, but because the limiting of information people can access is inherently undemocratic. Yet, there is common a dangerous acceptance of this idea when it comes to incarceration, particularly when it comes to ideas and books deemed controversial, challenging, or even dangerous.

Opposition to prison censorship must apply even to such literature containing challenging or controversial ideas. As in public schools or libraries, access to information and literature is a social responsibility, especially in a diverse culture where people have vastly different experiences of living. In such a pluralistic society, it is not possible to cultivate community without exposure to perspectives beyond one’s own, as well as information that can’t be acquired through individual, lived experience. Exposure to diverse voices, and new information and ideas is necessary for people in our culture to understand one another, appreciate the perspectives we all bring, and find common ground that enables us to coexist.

The State of Prison Censorship

Restricting access to literature has been a longstanding practice in U.S. prisons—but not an uncontested one. In 1969, the jailhouse lawyer Martin Sostre, imprisoned in Attica, filed a number of lawsuits against New York State prison officials for their censorship. He argued that these policies—such as a ban on Nation of Islam religious materials—were arbitrary and violated constitutional due process guarantees.6Sostre v. Otis, 330 F. Supp. 941 (United States District Court, S.D. New York July 28, 1971). According to Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin, who was incarcerated with Sostre in New York, prior to Sostre’s suits even the U.S. Constitution was considered contraband.7Lorenzo Kom’Boa Ervin, Lorenzo Kom’Boa Ervin and the Movement’s Beginnings, interview by David Marquis, Books Through Bars: Stories from the Prison Books Movement, 2024, University of Georgia Press. It was in the aftermath of Sostre’s legal victories that the first prison book programs were started, with volunteers in different communities collaborating to send books to incarcerated people at their request.8The earliest prison book programs, Books to Prisoners (Washington), Prison Book Program (Massachusetts) and Prison Library Project, were all founded less than five years after Sostre’s legal victories. Books Through Bars: Stories from the Prison Books Movement, edited by Moira Marquis and David Marquis, UGA Press, 2024.

But while Sostre’s efforts opened the door to challenging book bans in a court of law, the courts themselves subsequently adopted a largely deferential attitude toward prison officials’ book bans. As we noted in our 2019 report, Literature Locked Up: “The [leading] 1987 case Turner v. Safley established a ‘reasonableness’ test for evaluating the decisions of prison administrators, meaning that courts will uphold restrictions on an incarcerated person’s constitutional rights so long as the restrictions are reasonably related to the interests of incarceration.”9James Tager, “Literature Locked Up: How Prison Book Restriction Policies Constitute the Nation’s Largest Book Ban,” PEN America, September 24, 2019, https://pen.org/literature-locked-up-prison-book-bans-report/.

However, PEN America and other organizations have determined that the “interests of incarceration” standard has been applied at a scope and scale that far exceeds the denial of literature that even arguably could be used to escape from prison or enact violence. Empowering carceral authorities to limit the circulation of literature and ideas by asserting necessity has enabled prison censorship to target even the most innocuous and utilitarian of literature. Beginning as early as 1991 in Florida and New York, state departments of corrections started banning specific titles, which they deemed threats to the interests of incarceration. Today, nearly half of U.S. state prison systems have statewide lists of banned titles.10PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, 1999-2023 (Florida), 1999-2019 (New York), https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ

In addition, over the past several years there has been a steep rise in content-neutral policies that limit incarcerated people’s access to reading materials regardless of their content through “approved vendor” policies. These policies may block friends and family members, church and community groups, prison book programs, independent bookstores, and lesser-known publishers from sending books directly to incarcerated people. Such policies do not ban literature explicitly, but that is their effect. Idaho, for example, implemented new “approved vendor” requirements in 2021, resulting in a staggering 2,079 publications being blocked from August 2021 to August 2022.11List of rejected materials by vendor, Idaho Department of Corrections, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ.

The COVID-19 pandemic also saw an increase in prison censorship. In Washington state, for example, there were 280 instances of statewide banning of literature in 2019, 489 cases in 2020, and 635 cases in 2021, demonstrating a dramatic rise.12Publications Review Log, Washington State Department of Corrections, August 2022, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ. Censorship rose in Texas as well, with 1,092 books banned statewide in 2020 and 1,603 banned in 2021, increasing the number of rejected books by over 50 percent.13“Directors Review Committee Decisions,” Texas Department of Criminal Justice, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ.

Despite its pervasiveness, prison censorship is largely invisible to the public. Official documentation, including lists, policies, and procedures that prisons use to censor, are by and large unpublished. Publicizing this censorship has fallen to civil society groups and watchdogs. In 2019, Seattle-based Books to Prisoners, in collaboration with the Human Rights Defense Center, obtained banned lists from 21 states and published them on its website along with some explanations.14“Banned Books Lists,” Books to Prisoners, https://www.bookstoprisoners.net/banned-book-lists/ In 2022 The Marshall Project published lists of censored publications they obtained through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests from 18 states in a searchable database, along with an introductory article.15“The Books Banned in Your State’s Prison,” The Marshall Project, February 2023. The Marshall Project published database: https://www.themarshallproject.org/2022/12/21/prison-banned-books-list-find-your-state They obtained 24 lists through FOIA but, according to their methodology, only published 18 because at the outset because a primary goal was comparative analysis. Therefore, they omitted lists which did not have the information or structure that would enable cross comparison with other lists. However, they have indicated they will continue to edit the lists and publish more. Both the Books to Prisoners and Marshall Project initiatives raised the visibility of content-based bans, generating widespread news coverage and further raising public awareness of prison censorship.16“5 Things We Learned About Prison Book Ban Policies,” The Marshall Project, March 2023. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2023/03/16/prison-banned-books-policies-what-we-know#:~:text=Sometimes%2C%20appeals%20succeed

This report builds on this existing body of research. In addition to FOIA’d government documents, including lists of specifically banned titles, our research includes phone calls to prison mailrooms and narratives from incarcerated people, which collectively illuminate how prison censorship actually plays out on the ground–including the ways and extent to which such censorship is obscured or rendered invisible by lack of documentation by prison authorities.

Methodology

FOIA Requests: Between January and July 2023, PEN America filed public disclosure requests to every state department of corrections, the District of Columbia department of corrections, and the federal prison system.17Michelle Dillon advised on procedure given her experience in acquiring the 2019 lists for Seattle Prison Books and in collaboration with the Human Rights Defense Center. Where FOIA requests needed to be filed by in-state residents, PEN recruited individuals from our network and from prison book program contacts. FOIA requests were submitted either by email to FOIA personnel or through FOIA websites where they exist.

We asked all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons for their censorship policies, their lists of banned titles, and the number of appeals filed by incarcerated people and publishers. We also asked how many appeals were successful and whether there were training manuals for mailroom staff. An example of our FOIA request along with other research gathering documents can be found here.

Responses were entered into a FOIA response spreadsheet, which we have made publicly available.18PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ Official paperwork provided in response to those requests forms the basis of this report.

We analyzed policies for the existence of and criteria for content-based bans, the criteria for content-neutral bans, the identities of personnel involved in censorship decisions, and the processes for appeal.

Responses illuminated the partial nature of official records.19All states gave initial responses. However, New Hampshire, Delaware, and Tennessee did not respond with any further information. Policies for these states were able to be found on their websites, but no data about publication rejections was provided or publicly available. Every list received came from FOIA requests or prison book programs except for the Nebraska TCSI list which was received from The Marshall Project and New York’s list through 2019 which was provided by the NYCLU. While all states empower facility-level administrators to censor at their discretion, not all states require individual facilities to self-report these bans upward to central authorities. In states like West Virginia, facilities can create their own censorship guidelines and practices without disclosure to state authorities at all.20The Federal Bureau of Prisons does not keep a list of banned titles and neither do the following state prison systems: Alaska, Alabama, Arizona, the District of Columbia, Delaware, Hawaii, Indiana, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Maryland, Maine, Minnesota, Missouri, Mississippi, North Dakota, New Mexico, Nevada, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, West Virginia The federal government does not require self-reporting of federal prisons’ censorship either. This means that for about half of U.S. states and the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP),21This includes the two federal Communication Management Units where incarcerated people have extreme restrictions placed on all communication including phone calls and letters as well as reading materials. The Center for Constitutional Rights has noted these facilities are “shrouded in secrecy.” https://ccrjustice.org/home/get-involved/tools-resources/fact-sheets-and-faqs/cmus-federal-prison-system-s-experiment-group there is no centralized data at all on the specific titles or quantity of literature being censored.

To fill these data gaps and allow us to paint a more comprehensive picture of the reality of prison censorship on the ground, we supplemented our FOIA findings with additional research—surveying prison book programs, calling prison mailroom staff by phone, collecting narratives from incarcerated people, and drawing on our own firsthand experience sending book to incarcerated people.

- Surveying Prison Book Programs (PBPs): Most PBPs are volunteer collectives that send books to incarcerated people throughout the country.22“Books to Prisoners Programs,” https://prisonbookprogram.org/prisonbooknetwork/. PEN America asked them to report on the rate of returned packages they receive, the stated reasons for the returns, and whether they had capacity to follow up in their service areas. We circulated this survey through a LISTSERV comprising about 40 PBPs. 19 programs responded, representing literature distribution to prisons in all 50 states.23Average rate of returned packages from Prison Book Programs, determined through survey data collected by PEN America, 2023, https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1yW9wpzSPeCPf2HIfnXRbBf8q26v0z1m2SbpgHKxPZZs/edit?usp=sharing Since PBPs send books to incarcerated people, the information they provided offers insights into how censorship policies play out at the level of individual prisons.

- Calling Mailrooms: PEN America staff and volunteers called mailrooms in 16 target states.24Alabama, Arkansas, California, Connecticut, Georgia, Kansas, Maine, Minnesota, Montana, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Virginia, and Washington. These states were selected to represent geographic diversity, because there are a large number of private prisons or federal prisons in the state or because of the need to cross-reference state provided data or to fill in a lack of state provided data. We called 302 of the 517 prison mailrooms in these states. People at 262 facilities answered the phone and let us speak with the mailroom staff. We limited our calls and follow-ups to three attempts, after which we stopped trying that facility and moved on to the next. On these calls, PEN America staff and volunteers asked what criteria needed to be met for literature to be accepted by their facility. Our list of questions, along with our guidance for how to conduct their calls, is provided in this report’s appendix. Answers from this outreach were entered on a spreadsheet that compares this data with information that the Beehive Collective gathered using the same methodology in 2015.25PEN America Phone Calls to Facilities, July 2023-September 2023, https://airtable.com/app1VaFlQwzdtVgQ9/shrLpEfUn9eUiNzON. Beehive Collective https://beehivecollective.org/

- Collecting Narratives from Incarcerated People: PEN America mailed a call for submissions to 603 incarcerated people on our mailing list, requesting narratives of their experiences of carceral censorship. 62 people submitted narratives, 19 of these included original censorship paperwork as well as other bureaucratic justifications for censorship. We used inductive coding of responses for tone and content analysis, including what topics arose most frequently, such as contraband, mailroom staff, and appeals processes.26PEN America Prison Book Bans Narratives (Code by Content and Tone), 2022-2023, https://airtable.com/appXBNJTb75HmY5LC/shrvN4G1aX5L3V5wB. These narratives provide insight into how incarcerated people personally experience and perceive censorship, as well as undocumented prison practices.

- Drawing on PEN America’s Firsthand Experience: Perhaps uniquely, our research also includes our own experiences as a co-publisher and direct provider of the creative writing anthology, The Sentences That Create Us: Crafting a Writer’s Life in Prison. Through a grant from the Mellon Foundation, PEN America has distributed over 45,000 copies of this book for free to incarcerated people. The challenges we have faced in fulfilling incarcerated people’s requests for this text are also included in this report.

Our research focuses predominantly on prisons, the institutions where people are sent largely after they are convicted. This is opposed to jails, which, by and large, incarcerate people who have been charged, but not convicted, with crimes and are not able to access bail.27Jails can also be long term facilities as people fight their cases, however long people are actually detained in jail, they are all under guise of operating as short term facilities (i.e. “speedy” trial and sentences less than one year). Jails can also serve as immigration detention centers and house people who are awaiting prison assignment or who are being tried for another charge. Because jails and detention facilities are not subject to state-level prison policies issued by departments of corrections, and due to the transience of their populations, jails are often some of the most extreme censors. We recognize this and note the urgent need for additional research specifically on jails as well as prisons.

Section I: Content-based Bans

Content-based bans refer to the rejection of books because of the specific content within them—limiting incarcerated people’s access to information and specific ideas by designating them as threats. Arguments for content bans that may appear reasonable to an outside viewer, such as the contention that certain book content could be used to facilitate an escape, are routinely and speciously used to censor a truly astounding array of information and literature. Largely because the full extent of prison censorship is invisible or under-visible to the outside world, these rationales are rarely challenged, let alone critically evaluated.28Jeanie Austin et al., “Systemic Oppression and the Contested Ground of Information Access for Incarcerated People,” Open Information Science 4, no. 1 (January 1, 2020): 169–85, https://doi.org/10.1515/opis-2020-0013.

Obscuring Censorship: Record Keeping and Transparency

Civil society groups and civil rights watchdogs have struggled to track the current status of prison censorship in any one state, let alone their proliferation on a national level. The nonprofit Ithaka S+R researched banning practices and censorship policies, noting that “research and reporting on prison censorship policies remain largely localized, with few wide-scale, systematic studies of the issue.”29Pokornowski, Ess, et al. Security and Censorship. Ithaka S+R, https://sr.ithaka.org/publications/security-and-censorship/. Accessed 9 July 2023. Prison book programs have mostly tried to raise awareness locally when prisons implement new censorship restrictions for communities they serve.30Washington Corrections Officials Reverse Ban, Will Allow Prisoners to get Used Books in the Mail,” Seattle Times, April 10, 2019. https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/politics/washington-corrections-officials-reverse-ban-will-allow-prisoners-to-get-used-books-in-the-mail/ But these programs are largely run by volunteers and struggle to keep up with the demand for books even absent censorship. The upshot is that there have been few nationwide efforts to analyze trends in carceral censorship. This may be why, when news articles cover this phenomenon, they frequently address only one or a handful of states.31E.g. Polo, Michelle Jokisch. “Michigan Prisons Ban Spanish and Swahili Dictionaries to Prevent Inmate Disruptions.” NPR, 2 June 2022. NPR, https://www.npr.org/2022/06/02/1102164439/michigan-prisons-ban-spanish-and-swahili-dictionaries-to-prevent-inmate-disrupti. Sample, Brandon. “Seventh Circuit Upholds Ban on Dungeons & Dragons.” Prison Legal News, 2010, https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/2010/oct/15/seventh-circuit-upholds-ban-on-dungeons-amp-dragons/.

States With Centralized Banned Books Lists

PEN America’s FOIA requests, made to every state, the District of Columbia, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons, yielded 28 banned-book lists. While all these state and federal entities ban content, only 28 states keep lists of specific banned titles.32PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ Fifteen of these states’ lists give written rationales for the content-based censorship, identifying a specific reason for why each piece of literature on the list was banned. Thirteen states provided PEN America with lists without rationales—we know which literature is being banned there, but we do not have a record of the criteria being used to ban them.33PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ

PEN America was unable to obtain lists from two states—New York and Colorado—through our FOIA requests, even though we know that such lists exist.34Written response from Adrienne L. Sanchez, associate director of legal services at the Colorado Department of Corrections, March 7, 2023. Written response from Nadine Shultis, records access officer at the New York Department of Corrections and Community Supervision, April 25, 2023, July 24, 2023, September 5, 2023, & October 2, 2023. New York responded and indicated that records would be forthcoming but asked for money as well as three extensions, causing a total of six months of delay. The list that we use for this report’s analysis was provided by the New York Civil Liberties Union, which obtained it by threat of litigation in 2019.35PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ The Colorado Department of Corrections indicated that it had a list but could not disclose it because there are no maintained copies of the rejection notices sent to publishers, no maintained copies of appeals forms, and no report function for the database containing their list.36Bond, Michelle to Juliana Luna. Colorado Freedom of Information Act Request: Department of Corrections: Book Rejections and Impoundments. March 3, 2023. The Colorado list used in this report was obtained for Seattle Books to Prisoners and the Human Rights Defense Center in 2019 and listed 186 banned titles.37Dillon, Michelle. “Banned Books Lists” Seattle Books to Prisoners and Human Rights Defense Center. https://www.bookstoprisoners.net/banned-book-lists/

The states with the most banned titles, per their responses, are Florida (22,825 titles up to September 2023), Texas (10,265 titles up to February 2023), Kansas (7,699 titles up to 2021), Virginia (7,204 titles up to 2022), and New York (5,356 titles as of 2019).38New York Banned Publications, February 27, 2019, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ; Texas Banned Publications, through 2021, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ; Virginia Banned Publications, to 2022, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ; Kansas Banned Publications, to 2021, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ.

Of the 28 states that keep lists of banned titles, 3 reported that they regularly expunge the lists and begin anew as a matter of policy in order to provide ad hoc oversight. Pennsylvania and North Carolina reported that they completely expunge their content-based banned lists every year, and Oregon indicated that it does so every three years.39Bull, John to Juliana Luna. New Public Records Request: Juliana Luna. February 22, 2023. Public Records Request, DOC to Juliana Luna. Oregon FOIA Request: Mailroom Training Manual and Book Rejection Appeals. July 19, 2023. Filkosky, Andrew to Juliana Luna. Pennsylvania Right to Know Request: Department of Corrections: Book Rejections and Impoundments/RTKL 0339-23. May 3, 2023.

Reevaluation is supposed to lessen the arbitrariness or bias of censorship decisions. North Carolina adopted this policy in 2011 in response to a lawsuit against its DOC for censorship practices that included blanket denials of any literature deemed “gay.”40J. Phillip Griffin, Jr. of North Carolina Prisoner Legal Services, Inc. See: Urbaniak v. Stanley, U.S.D.C. (E.D. NC), Case No. 5:06-ct-03135-FL The department settled the case by agreeing to purge all past banned titles every year. This process, however, doesn’t solve the root issue that it claims to solve. While the purging of lists eliminates the previous judgments, it does not prevent prison staff from baselessly re-banning a book.

Even when states provided lists of banned titles with explanations, their practices were confusing. The Illinois Department of Corrections has two separate statewide lists: one of banned books and another of “Disapproved” books.41Illinois Banned Publications List, to 2022, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ; Disapproved Books List, to 2022, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ. Publications on both lists are forbidden in Illinois prisons, and it is not clear what the distinction is between these lists or why two lists are necessary. Vermont has taken the trouble to ban only nine books. The list includes a book on tying knots, The Art of War by Sun Tzu, and a book on the secretive signs and oaths of the Ku Klux Klan, written by a former member.42 Vermont Banned Publications, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ.

States Without Centralized Banned Books Lists

The remaining 23 states, D.C., and the Federal Bureau of Prisons use content-based censorship but do not keep centralized records of the censored titles.43Alaska, Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Utah, West Virginia, the Federal Bureau of Prisons. This includes Idaho which tracks literature rejected due to the distributor but not the title of the works, perhaps since the packages were never opened. See: PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ. The explanation for this lack of recordkeeping is that each piece of literature is evaluated case-by-case. Theoretically this means that mailroom staff examines each and every piece of literature that enters a prison and determine whether it violates one or more of the criteria outlined in state censorship policy. While states without centralized banned-books lists offer the possibility that a book can be banned in one facility and allowed in others, the case-by-case approach empowers individual facility staff to reject titles as they see fit, with no oversight. For example, New Mexico keeps records of book rejections through notification slips but does not consolidate these slips statewide.44The other states that keep records through notification slips, but do not consolidate on a statewide level are Alaska, Alabama, Arkansas, District of Columbia, Delaware, the federal BOP, Hawaii, Indiana, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Maryland, Maine, Minnesota, Missouri, Mississippi, North Dakota, New Mexico, Nevada, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, and West Virginia. See: PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ. New Mexico provided PEN America with copies of all its rejection slips for 2021, which we counted and sorted ourselves.45New Mexico DOC stated they would provide rejection slips from 2018-2023, but only paperwork from 2021 was ever provided. New Mexico is not included in the number of states that keep banned lists. Kentucky stated we would need to check with each individual facility to see what literature was censored, as there is no state oversight.46Inmate Correspondence, Kentucky Corrections Policies and Procedures, effective August 11, 2021, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ.

This results in some prisons, such as Northpoint Training Center in Kentucky and the federal prison in Chaparral, New Mexico, enacting extreme censorship with little accountability. Northpoint requires each piece of literature to be individually approved by a staff member whose name, position, and qualifications are not disclosed.47“Publications shall be rejected on a case-by-case basis.” Kentucky Corrections, Policies and Procedures. KRS 196.035, 197.020 ACA 5-7D-4487 through 5-7D-4496, 2-CO-5D-01. II 6. A. and McKinney, Carey, Classification and Treatment Officer, Northpoint Training Center, telephone interview by Moira Marquis, October 19, 2022. The federal facility in Chaparral simply has a blanket ban on all literature.48Otero County Prison, New Mexico, telephone interview with PEN America, June 16, 2023.

Book Banning Lists and Individual Facilities

Statewide lists are created not by high-level prison officials but by individual mailroom staff who intercept and inspect each piece of literature mailed to a prison. Such positions require only a high school diploma, and DOCs on the whole see high turnover—63 percent of people employed in the prison correctional field leave in under 2 years, and only 5 percent stay longer than 11 years.49American Correctional Association, The Office of Correctional Health. “Staff Recruitment and Retenion in Corrections: The Challenges and Ways Forward.” Corrections Today, 2023. https://www.aca.org/common/Uploaded%20files/Publications_Carla/Docs/Corrections%20Today/2023%20Articles/Corrections_Today_Jan-Feb_2023_Staff%20Recruitment%20and%20Retention%20in%20Corrections.pdf.

Big House Books, a prison book program based in Jackson, Mississippi, reported that the largest hindrance to sending books inside is “[t]urnover of prison mail staff that do not receive training on policies and procedures for allowance of books and do not understand that we are an approved service recognized by the department and the facility must accept our books because of a prior lawsuit settlement.”50Average rate of returned packages from Prison Book Programs, determined through survey data collected by PEN America, 2023, https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1yW9wpzSPeCPf2HIfnXRbBf8q26v0z1m2SbpgHKxPZZs/edit?usp=sharing

Narratives from incarcerated people commonly note that prison mailrooms appear to be understaffed or operating for very limited hours, inadequate for the amount of literature and mail review they are supposed to be sorting. Christopher Philmon, incarcerated in Texas, wrote to PEN America saying: “In just two years, the entire Mailroom Staff at this unit has been emptied, and replaced by completely new people three or four times. Each person is given permission to deny our books, mail, photos from home, magazines, anything that can come to us by mail.”51Letter sent from C.R. Philmon at James V. Allred Unit (Texas) to PEN America, April 12, 2023.

Over half of the testimonials we received from incarcerated people indicated that mailroom staff are widely perceived as inconsistent or inept. A third of respondents asserted that they were unnecessarily strict. Others told us that staff was apparently empowered to justify censorship with rationales that are absent from policy criteria.52PEN America Prison Book Bans Narratives (Code by Content and Tone), 2023, https://airtable.com/appXBNJTb75HmY5LC/shrvN4G1aX5L3V5wB.

The difference between a state that keeps a banned-books list and one that does not is merely whether a record of censorship is maintained and assessed by authorities outside the facility and whether the ban is statewide policy. With recordkeeping, it is possible to know the specific titles that mailroom staff rejects. Without it, there is no documentation of these determinations.

But even where recordkeeping exists, we found discrepancies. Numerous incarcerated people gave us examples of books that were denied to them even though they were not on the state’s banned-books list. They named titles such as Insider’s Guide to Prison Life in Michigan and Travels in My Land in Pennsylvania.53Letter sent from Bryan Noonan at Parnall Correctional Facility (Michigan) to PEN America, March 21, 2023. Letter sent from Ken Meyers at SCI Albion (Pennsylvania) to PEN America, April 30 2023.

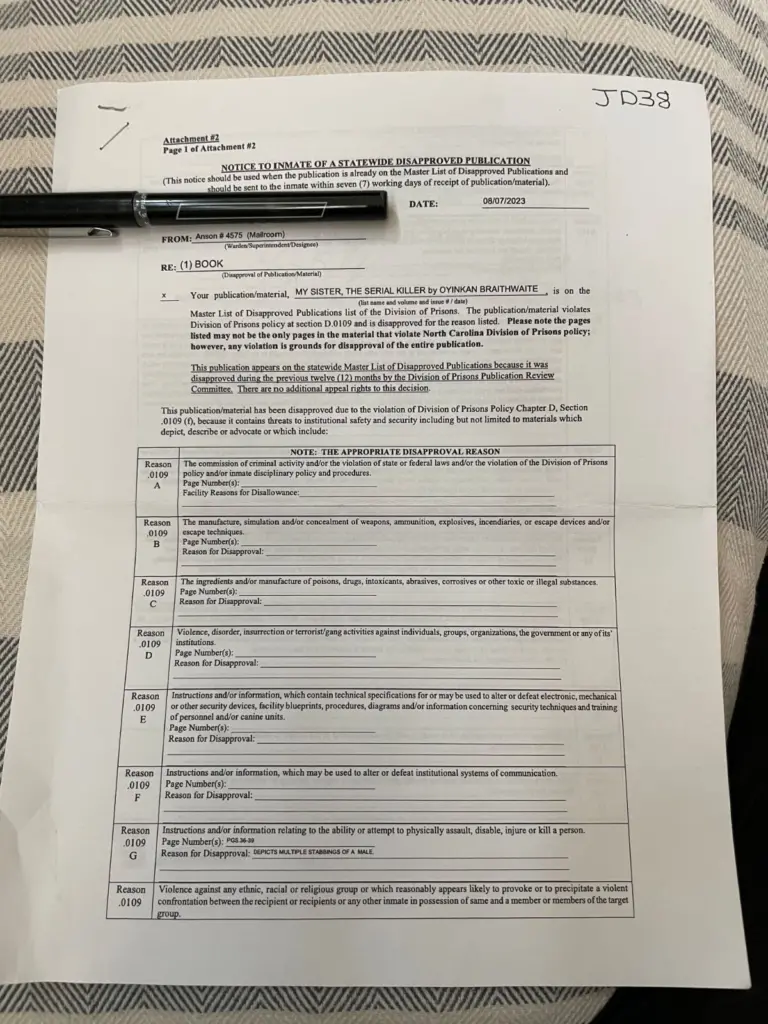

In September 2023, PEN America received paperwork from North Carolina, where the book My Sister, the Serial Killer was censored.54“Notice to Inmate of Statewide Disapproved Material,” North Carolina Department of Corrections, August 7, 2023. The information stated that the book was on the banned list in August 2023, but the title does not appear on the state’s cumulative list or on the annual list from that year.55Lists of rejected titles, Cumulative; List of rejected titles to 2019; List of rejected titles to 2023; North Carolina Department of Corrections, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ This would seem to imply either that mailroom staff at individual facilities in North Carolina are operating from a different list than the one PEN America was given or that the staff who filled out the paperwork mistakenly or misleadingly identified the book as banned. In either case, the literature did not reach its intended recipient, despite a centralized list and recordkeeping.

Main Rationales for Censoring Literature

While censorship policies are nearly universal—all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the Federal BOP have policies that outline the written content that carceral authorities are allowed to censor—every state and the federal government has its own criteria.56Delaware responded with initial receipt of FOIA requests but has not given further information. Tennessee stated in response to our FOIA “No such record(s) exists, and this office does not maintain record(s) in response to your request.” For these states, policies were obtained by PEN America online. New Hampshire, and Wisconsin released records in regards to our FOIA after request for comment. Washington D.C. stated records would be released to us after request for comment, but none were ever proffered. For more detailed information see: PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ Additionally, among the 15 states that censor content, recorded rationales for censorship decisions differ widely.57See lists from California, Connecticut, Florida, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Texas, Virginia, Washington, and Wyoming in PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ

Sometimes the listed explanation is just a code—a reference to the specific subsection of the relevant policy. For example, Florida’s banned-books list contains Anyone Can Draw: Create Sensational Artwork in Easy Steps, by Barrington Barber, and simply cites the codes 3J and 3M.58Going to their policy, we see 3J is: “It depicts nudity in such a way as to create the appearance that sexual conduct is imminent, i.e., display of contact or intended contact with a person’s unclothed genitals, pubic area, buttocks or female breasts orally, digitally or by foreign object, or display of sexual organs in an aroused state.” 3M states: “It otherwise presents a threat to the security, order or rehabilitative objectives of the correctional system or the safety of any person.” Florida Department of Corrections, 33-501.401 Admissible Reading Material. 0(2), acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ. Other times, there is no reference to censorship criteria but an explanation, as in Michigan’s list for Spanish at a Glance: “Threat to the good order and security of the facility, may be used by prisoners to learn to communicate in a language that staff at the facility does not understand.”59“Prisoner Mail,” Policy Directive, Michigan Department of Corrections, March 1, 2018, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rsU_TSc0sEP3mIGSU2xWx0y7ENe6nvcz/view?usp=sharing

Washington, Michigan, and Nebraska’s lists similarly contain paragraphs that give rationales but do not specifically align with policy coding. Washington gives lengthy explanations that sometimes include page numbers but often leave unclear what specific policy has been violated.60Publications Review Log, Washington State Department of Corrections, August 2022, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ; Michigan Rejected titles list to 2022, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ; In Iowa and Wyoming, only some titles have corresponding explanations.61“Iowa DOC Disapproved Publications,” June 2019, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ; Wyoming Warden’s Publication Rejections, October 26, 2022, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023. Nebraska, California, and Pennsylvania list only page numbers in their rationales for censorship.62Books banned in Nebraska, through 2022, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ; Books banned in Pennsylvania through 2022, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ; Books Banned in California, through January 1, 2023, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ.

To track the main rationales for censorship in the 12 states that keep lists with corresponding explanations that extend beyond page numbers, PEN America counted and recorded the stated reasons when possible. The most common rationale we found was “sexually explicit” or terms such as “Sexually Sugestiveve [sic]/Provocative,”63Montana List of Banned Publications, through 2023, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ. along with “nudity.” The second-most-common rationale was “security risk” or “threat to security.” This information, while useful as a snapshot of censorship practices, is necessarily incomplete, in regard to the specific content, given the limited number of states that track their censorship. What is clear by this analysis, however, is the irrationality of censored literature under the supposedly stated criteria.

Sexuality

Sexual content was the most common rationale for denying literature on all state lists except those from Florida and New Hampshire. Bans for purported sexual content were applied extremely broadly, from books on menopause to issues of Cosmopolitan and Rolling Stone to art and medical books.64Of the states that list rationales for their content bans, the highest overall number of titles banned for sexually explicit content are: Florida, Texas, Louisiana and Connecticut. For more, see: PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ For example, in 2007, Louisiana began keeping a list of banned titles that now totals 3,173 separate pieces of literature.65Books banned in Louisiana through 2023, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ. Overwhelmingly, the most common category for rejection was sexually explicit content, which accounted for 2,097 pieces. Of these, 17 were different issues of ARTNews, a magazine that claims to be the world’s oldest and most widely distributed art magazine.66Douglas, Sarah. ARTnews. Penske Media Corporation. https://www.artnews.com/.

In 2022, Texas banned 770 titles for sexual content out of a total of 1,236 banned titles.67Through 2021 Texas banned 4, 170 titles for being sexually explicit but further delineated the following categories which are also counted towards the censorship of sexual content: 567 titles banned for nudity, 1,271 for discussing rape, 217 for content related to incest, 135 labeled as indecency and 18 identified as necrophilia. Books banned in Texas to 2021, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ; and “Directors Review Committee Decisions,” Texas Department of Criminal Justice, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ. Half of New York state’s censored list (2,520 out of 5,356 titles through 2019) is rationalized as sexually explicit.68New York only turned over their censorship documents after a filing of briefs that threatened to sue for failure to comply with FOIL. Zoom conversation with Betsy Ginsberg and Antony Gemmell. Moira Marquis, August 1, 2023. Even in states, like Connecticut, where “sexual content” makes up a smaller percentage of banned titles (in a cumulative list beginning in 2012, 893 of 2,456 Connecticut’s banned titles are flagged for “sexual content”), the books included on these lists illuminate the overly broad application of this label: Williams Gynecology, second edition; Trans Bodies, Trans Selves; and Fairy Song: A Gallery of Fairies, Sprites, and Nymphs, a book of drawings.69Books banned in Connecticut, through 2023, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ; Werner, Claudia, Elysia Moschos, William Griffith, Victor Beshay, David Rahn, Debra Richardson, and Barbara Hoffman. Williams Gynecology Study Guide, Second Edition. 2nd edition. McGraw-Hill Education / Medical, 2012. Erickson-Schroth, Laura, ed. Trans Bodies, Trans Selves: A Resource by and for Transgender Communities. 2nd edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2022. S. Q. Productions, ed. Fairy Song: A Gallery of Fairies, Sprites, and Nymphs. SQP Productions, 2006. In Florida, literature flagged for both sexual content and security threats includes 365 Sex Moves, Esquire and Cosmopolitan magazines, Alchemy: The Secret Art, and The Girl with the Lower Back Tattoo, a memoir by Amy Schumer.70 Foxx, Randi. 365 Sex Moves: Positions for Having Sex a New Way Every Day. Quiver, 2012. Schumer, Amy. The Girl with the Lower Back Tattoo. Reprint edition. Gallery Books, 2017. Rola, Stanislas Klossowski de. Alchemy: The Secret Art. Bounty Books, 1974. Sebastian, Michael. Esquire. Hearst Corporation. https://www.esquire.com/. Pels, Jessica. Cosmopolitan. Hearst Corporation. https://www.cosmopolitan.com/.

Even policies that are specific are not applied as such. Texas’s censorship policy indicates that censoring literature for being sexually explicit is only permissible when literature is not “educational, medical, scientific or artistic.”71“Uniform Inmate Correspondence Rules,” Texas Department of Criminal Justice, June 25, 2021, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ Yet Texas’ list includes the international bestseller A Child Is Born, a photographic depiction of conception through birth written by a professor of obstetrics, which is banned for sexual content.72Nilsson, Lennart. A Child Is Born. Revised, Updated edition. Delta, 2004.

Prison officials’ justifications for blocking sexual content range from rejecting pornography because it could be used for “sexual gratification” to lists like New Hampshire’s that label some sexual content “obscene.”73“Resident Mail, Electronic Messaging, and Package Service,” New Hampshire, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ. While pornography is protected speech, obscenity is not, and New Hampshire’s distinction appears to be an attempt to affirm incarcerated people’s civil liberties.74 The Supreme Court ruled that pornography is protected speech under the first amendment in Miller v. California (1973) and Jenkins v. Georgia (1974). The U.S. Supreme Court established the test that judges and juries use to determine whether matter is obscene in three major cases: Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15, 24-25 (1973); Smith v. United States, 431 U.S. 291, 300-02, 309 (1977); and Pope v. Illinois, 481 U.S. 497, 500-01 (1987). Like First Amendment rights in general, however, incarcerated people’s access to pornography has been limited by courts. Where pornography has been banned, the cited rationale is frequently that possessing it creates a hostile work environment for female corrections officers in male prisons.75Reynolds, et al. v. Quiros, et al. 20-1158, (2nd Cir. 2022) https://www.courthousenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/ca2-opinion-ct-prison-porn.pdf It is noteworthy that the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) targets the victimization of incarcerated people by staff, rather than the reverse. “Prisons and Jails Standards: Prison Rape Elimination,” United States Department of Justice Final Rule, May 17, 2012, https://www.prearesourcecenter.org/sites/default/files/content/prisonsandjailsfinalstandards_0.pdf

Some states, including Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina, ban homosexual literature.76Ess Pokornowski, Kurtis Tanaka, and Darnell Epps, “Security and Censorship” (Ithaka S+R), 10–14, accessed July 9, 2023, https://sr.ithaka.org/publications/security-and-censorship/. Those three states still have anti-sodomy laws, which may be their justification for censoring gay literature.77Wakefield, Lily. “There Are 16 States in the US That Still Have Sodomy Laws against ‘Perverted Sexual Practice’. It’s 2020.” Black and Pink: PinkNews, January 24, 2020. https://www.thepinknews.com/2020/01/24/sodomy-laws-us-states-perverted-sexual-practice-lawrence-texas-louisiana-maryland-bestiality/. In Florida, the term “sexually explicit” is often used in tandem with codes 3M and 15P, which censor literature that “presents a threat to the security, order or rehabilitative objectives of the correctional system or the safety of any person.”78Florida Department of Corrections, 33-501.401 Admissible Reading Material. 0(2), acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ.

Fourteen testimonials from incarcerated people alleged that, in their experience, mailroom staff applied sexually explicit unreasonably. Dylan Jeffrey, incarcerated in New Mexico, wrote to PEN America, “I’ve also had numerous issues of The New Yorker rejected due to nudity in the cartoons, always absurdly innocuous drawings, as well as various magazines like Vanity Fair and Rolling Stone, usually for so-called sexual content in the advertisements.”79Letter sent from Dylan Jeffrey at Otero County Prison Facility (New Mexico) to PEN America, April 6, 2023.

Ted Point in Oregon pointed out the paradox that under our justice system, children can be sentenced as adults for the purpose of criminal liability, but adults cannot sexually gratify themselves—even when serving sentences of life without parole. He wrote, “What kind of a system would give a 14-year-old a ‘life sentence’ . . . yet not allow an adult to view the naked beauty of the opposite sex?”80Letter sent from Ted Point (a pen name) (Oregon) to PEN America, March 2023.

Stevie Wilson, incarcerated in Pennsylvania, and Michael Sutton, in North Carolina, point out that facilities ban literature while allowing television, film, and video games that frequently depict nakedness and sexual acts more graphically than the written content that is denied.81PEN America virtual Interview with Stevie Wilson, Pennsylvania, June 14, 2023; Letter sent from Michael Sutton at Nash Correctional Institution (North Carolina) to PEN America, undated. Robert Blankenship, incarcerated in Virginia, notes that in Virginia prisons, the Game of Thrones novels are banned but his prison airs the full, unedited HBO series on the facility televisions.82Letter from Robert Blankenship at Keen Mountain Correctional Center (Virginia) to PEN America, June 26, 2023. Blankenship is currently suing the Virginia DOC for prohibiting him possessing his own book manuscript and legal documents related to it. The department has justified this by designating the materials sexually explicit.837:23CV00183” Blankenship v. Clark, 7:23CV00183, (W.D. Va. Jun. 20, 2023): https://casetext.com/case/blankenship-v-clark This focus on limiting literature, especially for content that is widely available in mainstream media, represents a direct attack on the written word—and a corresponding fear of the thoughts, feelings, and reaction it might spark—rather than even a specious moral correction.

Security

The second-most-cited reason on state banned-books lists is that the material poses a “threat to security.” This designation sounds reasonable enough that it rarely receives public scrutiny. But even a cursory investigation of banned titles reveals that, as with content blocked for sex, security designations are applied to a wide variety of content that would be more accurately characterized as educational.

In Connecticut security concerns are cited in censoring 334 titles. Among these titles are “Men Unlearning Rape,” a 10-page rape-prevention guide, and My Body, My Limits, My Pleasure, My Choice, which explains sex positivity and encourages sexual empowerment as a means to stop cycles of harm.84Books banned in Connecticut, through 2023, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ; Biernbaum, Michael, and Joseph Weinberg. Men Unlearning Rape. Longmont, CO: Little Sages Books, 1991. Generation Five. My Body, My Limits, My Pleasure, My Choice : A Positive Sexuality Booklet for Young People. San Francisco: Generation Five, 2006. In Louisiana, security was cited as a rationale for censoring 584 titles, including the book Don’t Touch Me! Say No to Sexual Harassment.85Books banned in Louisiana through 2023, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ; Baker, Orvie B. Don’t Touch Me! Say No To Sexual Harassment. Einmalig Group, LLC., 2012.

The Florida prison ban of PEN America’s creative writing anthology The Sentences That Create Us is a clear example of how the security rationale can be leveraged incredibly broadly—and without accountability. In April 2022, Florida’s Literature Review Committee banned the anthology, specifically designed to assist incarcerated writers in fostering their craft, as a threat to security by under the following rationale: “Otherwise presents a threat to the security, order, or rehabilitative objectives of the correctional system or the safety of any person.”86Meeting Minutes, Florida Literature Review Committee, April 21, 2022, acquired by PEN America via FOIA request, https://docs.google.com/document/d/17Y_43JJi1teTwXWMnCDwxLcJQeS6oXsE/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=101919545278643152106&rtpof=true&sd=true. There was no explanation of how this creative writing book would threaten a carceral facility’s security.

Security is cited as the rationale for the most censored title in the country. Prison Ramen is a cookbook that offers ramen recipes that people can make in their cells and is banned in 19 state prison systems.87PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ Before each recipe is a brief story that explains how the recipe was created or describes a particularly meaningful time this meal was eaten. Most contributors were incarcerated at some point in their lives—some just for a night—including Danny Trejo, Slash, Shia LaBeouf, and Clarence J. Brown III, an actor featured in The Shawshank Redemption.88“‘Prison Ramen Gives a Taste of Life Behind Bars,” Here & Now, WBUR, November 3, 2015, https://www.wbur.org/hereandnow/2015/11/03/prison-ramen; Erin Mosbaugh, “How One Ex-Con Found Redemption through Ramen, and Created a Cookbook of Prison Recipes,” First We Feast, October 28, 2015, https://firstwefeast.com/eat/2015/10/prison-ramen-cookbook-shia-labeouf.

States offer several rationales for banning Prison Ramen but all fall under the umbrella of security concerns: Virginia for referencing prison hooch,89Virginia Banned Publications, to 2022, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ Montana for referencing razor blades,90Montana List of Banned Publications, through 2023, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ. Connecticut for “instructing on the commision [sic] of criminal activity.”91Books banned in Connecticut, through 2023, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ. Washington cited the descriptions of removing food from the cafeteria as well as references to cell phones and to the false belief that tomato plant leaves can be used to poison someone.92Publications Review Log, Washington State Department of Corrections, August 2022, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ.

As Prison Ramen demonstrates, content-based bans frequently target literature that details what life is like inside prisons. If knowing about prison life is a threat to security, then that threat is already pervasive, since no one who lives in a prison is somehow exempt from knowing what happens inside those walls. Meanwhile, these books that are blocked as “threats” could play a major role in validating incarcerated people’s experiences, making them feel less alienated, and encouraging empathy—the benefits of which should be obvious.

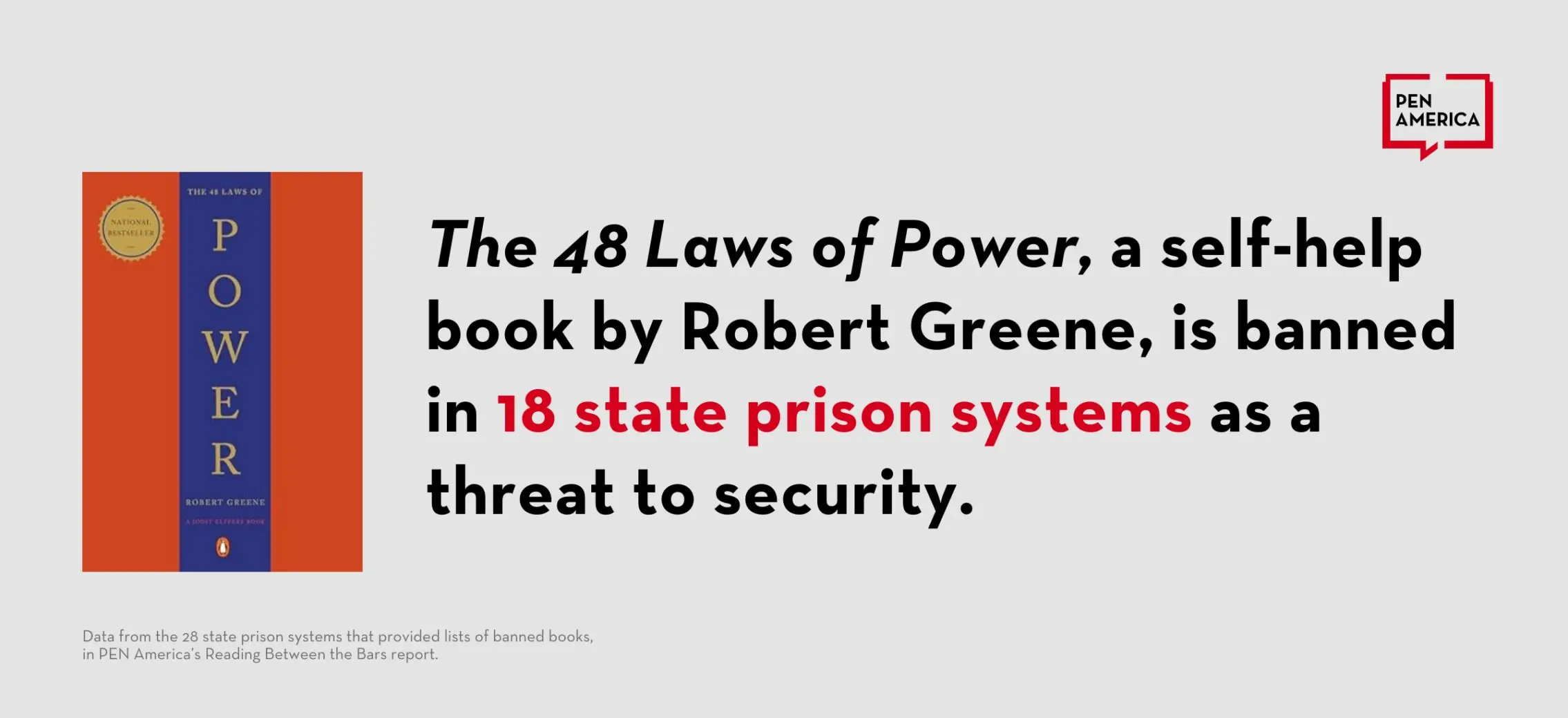

In prisons across the United States that track content bans, the most banned author is Robert Greene, whose many New York Times bestsellers are also commonly cited as threats to security. His best-known book, The 48 Laws of Power, is banned in prisons in 18 states.93PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ It analyzes the nature of authority and the power dynamics behind all kinds of interpersonal social relationships, from friendships to romantic relationships to more hierarchical social structures. Greene told PEN America that he has been contacted by incarcerated people who were terrified by prisons before they read his book. “The correspondence that I got,” he said, was “about the system, and how it was affecting them and how it was kind of making them paranoid, and making them think that everybody was against them, etc., etc. And they didn’t know how to deal with it. And the book just kind of calmed them down and made them reflect and not react emotionally to these situations.”94Robert Greene, in discussion with the authors, Zoom, July 26, 2023.

Greene said that his books are intended to help people understand that others’ treatment of us is largely about them, not a simple reflection of ourselves.95Robert Greene, in discussion with the authors, Zoom, July 26, 2023. Corrections departments interpret Greene’s books completely differently. Washington banned The 50th Law of Power, co-written with musician 50 Cent, claiming that it is, “[p]romoting ‘using’ certain maneuvers to manipulate and deceive others, teaching how to’s to intitiate [sic] others to work with or for you using a mission statement to disguise the extent and source of power, and psychology or nuances of others needs and demands, all of which might be used in illegal activities in a prison.”96Publications Review Log, Washington State Department of Corrections, August 2022, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZQ.

James Mancuso, incarcerated in a for-profit prison in Idaho, wrote to PEN America about The Laws of Human Nature, another book by Greene: “I don’t see The Laws of Human Nature posing a real threat to the safety and security of the facility. It doesn’t promote disorder or violence. Nor does it describe how to escape or teach someone to build tools to escape prison. Well, unless the Chief of Security thinks learning empathy and modifying negative behaviors is a tool to escape prison.”97Letter sent from James Mancuso at Saguaro Correctional Center (Idaho) to PEN America, April 10, 2023.

Of course, speaking, writing, and reading can all theoretically be used to commit criminal acts or escape from prison. But this theoretical possibility does not justify prohibiting incarcerated people from engaging in them. Similarly, incarcerated people should have the same right to self-help books as anyone else. Assuming that self-actualization techniques will be used for nefarious purposes denies one of the purported goals of incarceration: rehabilitation.

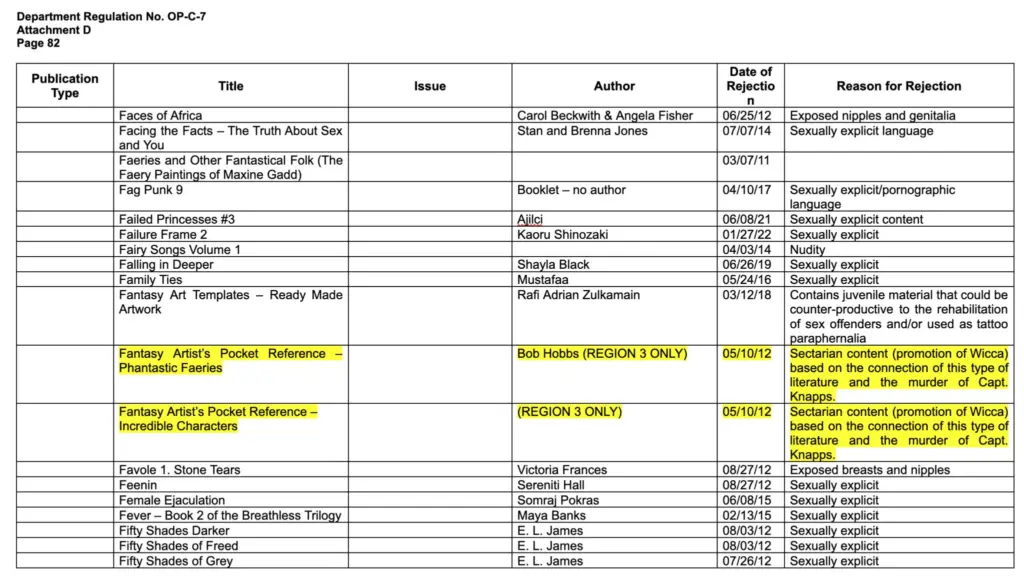

Prisons regularly apply such speculative, myopic reasoning when citing security concerns to ban other genres of literature as well. Books on magic and content such as Fantasy Artist’s Pocket Reference: Incredible Characters, are often censored for purported security concerns.98Cowan, Finlay. Fantasy Artist’s Pocket Reference, Incredible Characters: Draw, Paint and Create 100 Beings of Myth and Imagination. Cincinnati, OH: A David and Charles Book, 2007. As are books on mind control, shape shifting, and Dungeons & Dragons role-playing.99Montana List of Banned Publications, through 2023, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ. A particularly strange example appears on Louisiana’s censored list, which explains its ban of Fantasy Artist’s Pocket Reference by noting, “Sectarian content (promotion of Wicca) based on the connection of this type of literature and the murder of Capt. Knapps.”100Books banned in Louisiana through 2023, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ. Captain David C. Knapps was a corrections officer at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, on the site of the former Angola Plantation,101Sack, Kevin. “2 Die in Louisiana Prison Hostage-Taking.” The New York Times, December 30, 1999, sec. U.S. https://www.nytimes.com/1999/12/30/us/2-die-in-louisiana-prison-hostage-taking.html. Ryan, Joanne, and Stephanie L. Perrault. “Angola: Plantation to Penitentiary.” Preserving Louisiana’s Heritage. New Orleans District: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 2007. https://www.crt.state.la.us/Assets/OCD/archaeology/discoverarchaeology/virtual-books/PDFs/Angola_Pop.pdf. who was killed in 1999 during a prison uprising. It is unclear how this incident is linked in the minds of the mailroom staff to this book and Wicca.

This particular ban illustrates a paranoia that seems pervasive. Do carceral authorities believe that magic is real? Regardless, the expansive application of security concerns to tamp down on creative thinking and imagination should give us pause.

Non-English Language

Security is also commonly cited as the rationale for banning non-English-language literature. In 2022, the Michigan Department of Corrections attempted to ban Spanish and Swahili materials from all state prisons, arguing there could be secret messages hidden in the text the staff could not decipher.102Michelle Jokisch Polo, “Michigan Prisons Ban Spanish and Swahili Dictionaries to Prevent Inmate Disruptions,” NPR, June 2, 2022, sec. Books, https://www.npr.org/2022/06/02/1102164439/michigan-prisons-ban-spanish-and-swahili-dictionaries-to-prevent-inmate-disrupti. Several states, including Washington, Florida, and Virginia, ban non-English literature entirely.103Mail for Individuals in Prison, Washington Department of Corrections, February 9, 2022, DOC 450.100, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ; Florida Department of Corrections, 33-501.401 Admissible Reading Material. 0(2), acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ; Offender Management and Programs, Operating Procedure 803.2, Incoming Publications, Virginia Department of Corrections, December 1, 2022 acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ. In 2022 Montana banned a book in American Sign Language for security purposes.104Montana List of Banned Publications, through 2023, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ.

John Corley, incarcerated in Louisiana, describes his facility’s rejection of an Italian-language coursebook that was cited as a security concern.105Letter sent from John Corley at Louisiana State Penitentiary (Louisiana) to PEN America, April 12, 2023. He said that he was informed of the denial and appealed it but that it was upheld throughout the chain of command. Corley wrote: “The written reply indicated that inmates were prohibited learning, teaching, writing, and otherwise communicating in a foreign language. . . . [The deputy warden of programming] told me the warden did not want a bunch of prisoners speaking in languages his officers could not understand.” After he sued the prison, he said, the authorities relented and gave him the book.106Letter sent from John Corley at Louisiana State Penitentiary (Louisiana) to PEN America, April 12, 2023.

Race

A category termed “racially inflammatory” was the third-most cited on Louisiana’s censorship list. Of the 144 banned titles noted by PEN’s review, only 4 were white supremacist content. In Louisiana prisons, the great majority of content banned as “racially inflammatory” comes from Black and brown authors, often in texts that critically examine racism. Such titles include The Black Panther, The Final Call (the Nation of Islam’s newspaper), Understanding the Assault on the Black Man, Black Manhood and Black Masculinity, We Do this Til We Free Us, 100 Years of Lynching, Terror in the Night, and Revolutionary Suicide.107Books banned in Louisiana through 2023, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ.

As PEN America previously documented in Literature Locked Up in 2019, literature that acknowledges the realities of racial violence are disproportionately targeted for censorship under the justification that they create social division.108James Tager, “Literature Locked Up: How Prison Book Restriction Policies Constitute the Nation’s Largest Book Ban,” PEN America, September 24, 2019, https://pen.org/literature-locked-up-prison-book-bans-report/. This has also been the case in efforts since 2021 to prohibit discussions of race or critical race theory, in public schools, colleges, and universities, which PEN America has documented extensively.109Jonathan Friedman and James Tager, “Educational Gag Orders: Legislative Restrictions on the Freedom to Read, Learn, and Teach,” PEN America, November 8, 2021, https://pen.org/report/educational-gag-orders/; Jeremy C. Young, Jeffrey Sachs, Jonathan Friedman, “America’s Censored Classrooms,” PEN America, August 17, 2022, https://pen.org/report/americas-censored-classrooms/.

Other states that cite racially inflammatory material as a rationale for censorship include Kansas, which bans James Baldwin’s I Am Not Your Negro for “racism/inciting” and Germany’s Black Holocaust 1890–1945 for “inciting hate and racism.”110Books banned in Kansas, through 2021, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ Michigan cited this category when it banned Franz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks—widely considered a leading psychological examination of the damages of racism and colonial hierarchies—claiming that the book “advocates for racial supremacy.”111Books banned in Michigan, to April 12, 2022, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ. Montana has banned The Making of a Slave for being “racial.”112Montana List of Banned Publications, through 2023, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ.

Stevie Wilson, incarcerated in Pennsylvania, argues that the denial of literature specifically is tied to the fear of a more mentally active incarcerated population. Carceral authorities, he writes, “just don’t want incarcerated folx to have books. [We] have video games, movies, tv, but no books. [They] just don’t want people to be thinking critically.”113PEN America virtual Interview with Stevie Wilson, Pennsylvania, June 14, 2023.

Examining content-based censorship lists reveals the recklessness with which literature is denied to incarcerated people. The criteria delineated is applied so broadly as to be effectively unmoored from its purported rationale and strains rational understanding.

Section II: Appeals Processes

Rubber Stamping Censorship?

When a piece of literature is censored due to its content, most censorship policies require prison authorities to give the intended recipient a standardized form that explains the stated rationale.114See Connecticut, Florida, Maryland as examples in PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ. This form also commonly outlines the steps for appealing the censorship. Incarcerated people are allowed to file appeals in almost every state. In some, such as Florida, Texas, Rhode Island, and South Carolina, the censored literature is automatically given to a central committee for review.115Florida Department of Corrections, 33-501.401 Admissible Reading Material. 0(2), acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ; “Uniform Inmate Correspondence Rules,” Texas Department of Criminal Justice, June 25, 2021, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ; Chapter 10: Inmate Life, Part 1 – Inmate Mail, Policy and Procedure, Rhode Island Department of Corrections, 24.01-7 DOC, August 8, 2016, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ; Inmate Correspondence Privileges, South Carolina Department of Corrections, PS-10.08, September 6, 2022, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ. This means that while incarcerated people do not have to file paperwork, they also are unable to provide a rationale as to why the material should be permitted.

An incarcerated person can only appeal content-based bans that affect them personally, and only when the initial censorship is documented—if an incarcerated person does not receive formal notification that their book was blocked from reaching them, they have no recourse to appeal.

Publishers or distributors, which have First Amendment rights that protect them from acts of censorship, can file their own appeals. Most states have written policies that require publishers be notified of a rejection.116“5 Things We Learned About Prison Book Ban Policies,” The Marshall Project, March 2023. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2023/03/16/prison-banned-books-policies-what-we-know#:~:text=Sometimes%2C%20appeals%20succeed Even so, many publishers and bookstores do not have the resources or staff needed to contest prisons’ censorship of their publications.

Often the appeals paperwork must be filed within a tight time frame, spanning from days to weeks, and in some states, like Pennsylvania, incarcerated people are charged a fee to file the appeal.117Inmate Mail and Incoming Publications, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, DC-ADM 803, August 3, 2020, acquired by PEN America via FOIA Request, PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ; Once appeals are filed, the processing differs widely by state. Sometimes facility staff review the appeal and decide whether to accept it before appeals are evaluated by state-level review.118Illinois, Rhode Island and Ohio use this method, among other states. See: PEN America Index of Prison Censorship through State Documents 2023, https://airtable.com/appIhuRjYftpulgc7/shrTAS7blzY92NZZ